It is said that the spirits of all past rebellions are present when revolutionary aims are finally achieved. However the path from rebellion to revolution is not as linear as the line of questioning suggests. It is not a given that all rebellions naturally lead to future revolution. This essay will contend that the path to revolution is multiple; with rebellion not being a necessary precondition to revolution nor the most impactful form of political violence to revolution. However, the history of rebellion within a given society is a significant multiplier of the likelihood of future revolution. Secondly, the impact of rebellion upon future revolution is dependent upon the characteristics of said rebellion; in particular the disloyalty of the military, great power support for the regime and the relative unity of the rebels. Finally, the advent of Nationalism and its impact upon the framing of rebellion is discussed, which often leads to more successful outcomes. Overall, it can be concluded that rebellions do not ‘become’ revolutions themselves but rather ‘influence’ future revolutionary action, with the nature of influence being dependent upon the existence of specific factors within the character and context of rebellion.

Literary discrepancy

Before engaging in the main body of this essay, I think it is important to define the terms of the debate, as there is a wide variety of definitions of rebellion and revolution which can change the nature of connection between the two concepts. Revolution in the context of this essay can be considered ‘a fundamental change in government, brought about by violence, often involving social groups ordinarily excluded from power’ (Stuart & Cowie, 2021). Rebellion can be defined as an organised direct threat to the continuation of a current regime through violent means, that often does not achieve its revolutionary goals. Furthermore the distinction between mass rebellion and elite rebellion has to be made; with the former being rebellion led by those outside of the existing power structure, and the latter being within. Most rebellions however are facilitated by the interplay of both of these in one way or another.

The path to revolution is multiple

Within the question title, the assumption is made that rebellion is the only and most successful form of political violence that leads to revolution. This assumption cannot be adequately supported, and furthermore is actively undermined by the existing literature. Revolution within a given polity can be achieved through a number of forms of political violence including; war, civil war, riots, coups and rebellion. Of all these forms, it can be seen that rebellion has not had a considerable impact historically on the development of revolution. Russell (1974) finds that between 1900-70 28 mass rebellions took place, and of these 28 only 12 resulted in the capture of political power. Building directly from this, Walt (1992) finds that of the 12 successful mass rebellions, only 4 actually led to revolutionary change. This quantitative data brings Weede & Muller (1998, p. 49) to the conclusion that “…most mass rebellions fail to succeed in overthrowing the ruling class or the established regime…most of them fail to generate sufficient structural change to be called ‘revolutions’.” Indeed these findings are damning for the case of rebellion, as comparatively Taylor & Jodice (1983) find that in the period of 1948-77 alone 542 coup d’etat, usually conducted by the military, had occurred with 238 being successful; leading to revolutionary changes. Although a coup d’etat could be seen as a form of elite rebellion, it will not be counted as such (a coup d’etat is also just a form of coup), as usually these do not aim to bring about revolutionary changes, and are rather more concerned with societal & governmental stability; a polar opposite to revolution. Indeed Taylor & Jodice (1972: 1983) themselves describe a coup d’etat as an “…irregular power transfer.”

However, this does not mean that rebellion has no ability to lead to revolution. It can be seen that the occurrence of rebellion is still a significant multiplier in catalysing revolution. The Cuban revolution is a prime example of this; previous to Castro’s own movement, Cuba had a long history of rebellion against authority, particularly against Spanish colonial rule from 1868-98. Although indirect to the Cuban revolution of 1959, these rebellious acts had both symbolic and practical implications; both the development of rebellious spirit within the people of Cuba overtime, and the development of assets that would aid future rebellion. For example, the creation of ‘guerilla paths’ across rural Cuba which became vital to the success of Castro’s own guerrilla movement against Batista in 1959. Even Castro’s own rebellious acts can be seen to directly link to his revolution; the attack on Moncada barracks in 1953 arguably directly catalysing revolutionary fervour within Cuba, with some even denoting this as the beginning of the Cuban revolution. Therefore, although rebellion is not a necessary precondition to revolution, its existence can have a positive multiplying effect upon the likelihood of future revolution.

The nature of rebellion

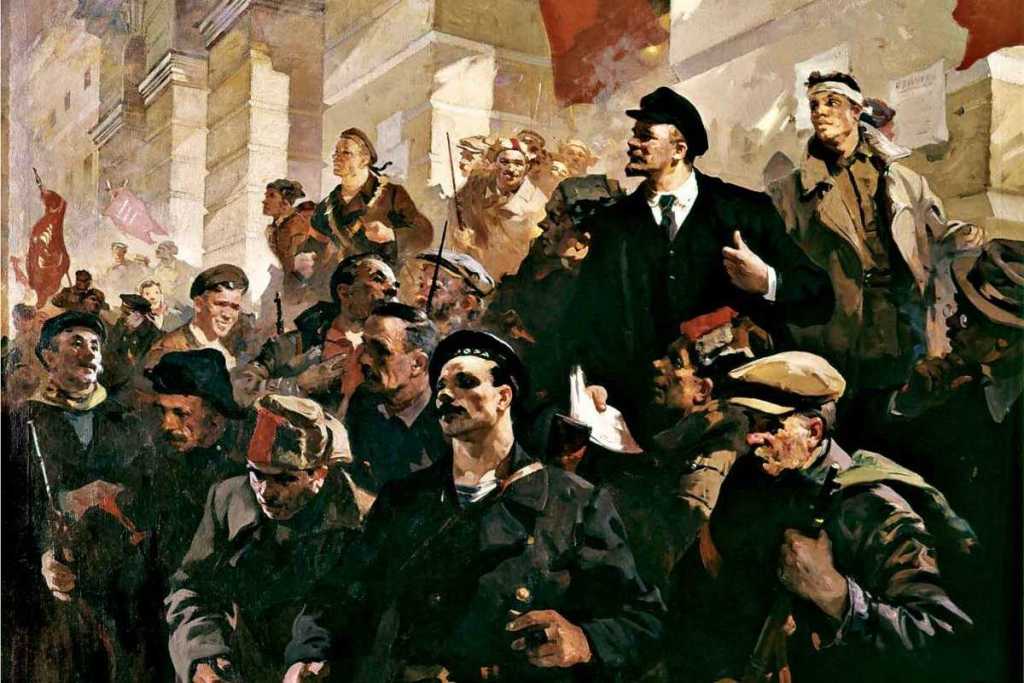

Thus far it has been ascertained that rebellion does not ‘become’ a revolution directly, but rather positively influences the rate at which revolution is reached. The degree to which this influence is direct, is determined by three significant factors; military disloyalty, great power support and rebel unity. Firstly, Russell (1974, p. 79) contends that “Armed Force disloyalty is necessary for a successful outcome of rebellion…”. Indeed, this view can be seen to play out during both Russian revolutions of 1917 where mutiny within the armed forces was vital to boosting the ranks of the budding Soviets across Russia, and further ensuring success during the following civil war. This is further qualified by Chorley (1943, p. 243) who in one of the earliest studies conducted found that “In a revolutionary situation, the attitude of the army is…of supreme importance.” Secondly, DeFronzo (1991, p. 170) finds that great power desertion of client states signals revolutionaries to redouble their efforts of rebellion, as in the case of Cuba, where the US stopped arming Batista’s forces before the advent of revolution. Additionally to this, Weede & Jodice (1983 p. 54) contend that previous support given to regimes by great powers already has a delegitimizing effect, creating a negative correlation between itself and the tendency for revolution, or rebellion at a minimum. Finally, the level of unity within rebel groups, both physically and ideologically is paramount to the translation of rebellion into revolution. Indeed it is of vital importance that rebel groups are homogeneous militarily, primarily in order to adequately compete with regime forces, as the technological gap present could be considerable. Ideologically rebel groups most often fail when made of a loosely held coalition of groups, who have vastly different visions for the political future. This point can be illustrated through the English Revolution, in which the Parliamentarians were both organised militarily (New Model Army as an example of this) and were united within their desire to discontinue the practice of absolute monarchy. The existence of these three factors is essential to the successfulness of rebellion, and significantly increases the probability of rebellion having revolutionary consequences. (1200 words)

National liberation movements

Lastly it can be said that more often than not, rebellions are initiated by those with altruistic motivations. In a lot of cases the source of this motivation can be found in nationalistic sentiments of liberation and self-determination. Indeed, Weede & Jodice find that nationalism is only second to religion as the most potent source of altruism. This finding is of considerable value, as nationalistic propaganda seems to improve the solidary recruitment to revolutionary movements, which we have seen previously is in part vital to successful rebellions (1998, p. 56). This is further supported by DeFronzo (1991, p. 314) as he points out “The Cuban, Nicaraguan and Iranian revolutions were like the Vietnamese in the sense of being viewed as national liberation movements.” Therefore the framing of rebellious movements as efforts to liberate the nation from corrupt control or foreign intervention are highly important for successful rebellions and by extension, revolutionary change.

Conclusion

Overall, it can be seen that rebellion is just one form of political violence that can initiate revolutionary change. Although it is a significant factor in increasing the chances of successful revolution, rebellion is by no means the most effective method. Yet, when rebellion does create revolutionary change, the presence of military disloyalty to the regime, great power support (and lack thereof) and rebel unity are critical characteristics. Finally, national liberation framing can have significant importance for both the specific recruitment of the military into revolutionary ranks, and overall support for the movement, increasing the chances of success. Through this short essay, the connection between rebellion and revolution have been discussed, with specific focus upon the nature of successful rebellion and the context in which it often occurs. However, much more detailed research is needed upon the topic area, specifically into pre-20th Century revolutionary history, which I admit was not fully explored within the bounds of this study.

Bibliography

Chorley, K. (1943). Armies and the Art of Revolution. London: Faber & Faber.

DeFronzo, J. (1991). Revolutions and Revolutionary Movements. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Russell, D. E. H. (1974). Rebellion, Revolution and Armed Force. New York: Academic Press.

Taylor, C. L. & Jodice, D. A. (1983). World Handbook of Political and Social Indicators. 3rd edn. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Weede, E., & Muller, E. N. (1998). Rebellion, Violence and Revolution: A Rational Choice Perspective. Journal of Peace Research, 35(1), 43–59.

Walt, S. M. (1992). ‘Revolution and War’, World Politics 44(3): 321-368.