Jim Crow. Two words that encapsulated over a century of discrimination against black Americans on the federal, state and county levels of governance. By 1900 after the failure of the Re-Construction Era to plot any long term plans for civil equality between black and white, Jim Crow was in full effect, disenfranchising black Americans from every aspect of US civil society. However, Jim Crow was not borne out of a vacuum; rather it was the product of long term racial social customs developed since the advent of slavery on the East Coast. This essay will contend that systemic Jim Crow was created by a symbiotic relationship between low white society and de facto attitudes, which influenced high white politics and therefore acted as the impetus for the creation of de jure legislation.

The reciprocal relationship will be explored with specific focuses upon the dualistic impact of both anti-black and pro-white legislation, as well as the role of terrorist organisations such as the KKK in maintaining hysteria within black communities to prevent major black organisation against Jim Crow. What should be particularly remembered in this context is the horrific violence experienced by the black community in this era, as a result of Jim Crow; not just legal segregation. Whilst a specific focus will be given on the time period 1877-1900, it is contextually paramount that we see Jim Crow as reaching much further back into the 19th Century for its origins as well as the lasting effect it held well into the 20th Century that necessitated the 2nd period of Civil Rights in the US. Equally, on a geographic scale this essay will maintain focus on the heart of Jim Crow; the Southern states.

Jim Crow De Facto Origins

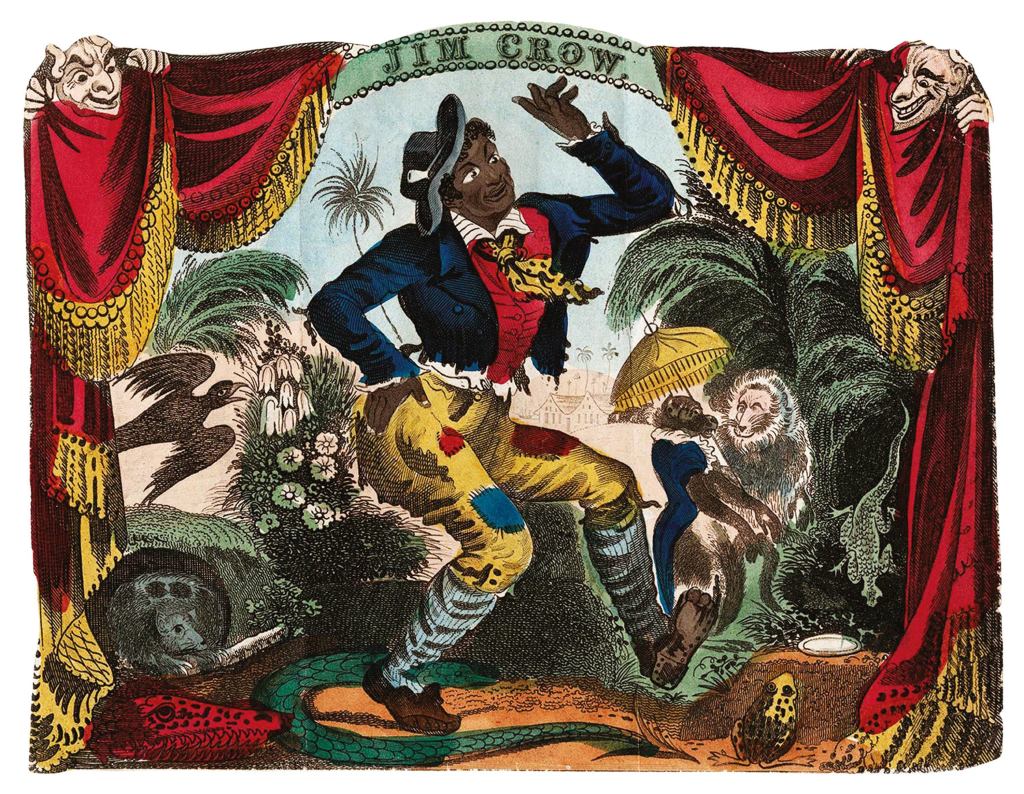

Jim Crow is an idea borne out of the psychology of slavery. When the first African slaves were brought to American shores in 1619, they were brought with the idea that they were less than human; uncivilised; unable to comprehend the ‘greatness of European society’ – and so were forcibly made into millions of cogs in the proverbial American socio-economic wheel. This foundation was built upon in the psyche of the settlers that became known as Americans for the next 200 years.[1] Jim Crow holds its origins in the psyche of an inferiority-superiority social complex, yet was birthed not as common conceptions hold (in the legal discrimination) but in 17,18 & 19th Century social connotations – Crow had been used as a term to refer to black Americans since the 1600s; ‘Jim’ or ‘Jimmy’ referred to a crowbar in the same era (connotations of criminality). However, primarily the original myth was disseminated through American society through ‘Jump Jim Crow’ a performative act by a white entertainer in blackface in order to belittle and demean black Americans, first performed in 1828.[2] These interpretations of black Americans were widely disseminated across society, as it will be seen the Northern Federal Government & Supreme Court were not shy to enact and support anti-black legislation, yet these social norms were nowhere more powerful than the South.

Even after the death of the Confederacy, in the face of a Union victory in 1865, the mentality of racial hierarchy maintained across white society through all economic classes. This aspect of Jim Crow cannot be stated more crucially for its impact upon the future of American race relations in the postbellum period. Jim Crow as a descriptive and encapsulating phrase for US race relations truly came into its own in the post-war era. As Union soldiers were stationed in the South, enforcing and changing the constitution to equally represent citizens, stripping the South of its bid for full autonomy and tearing its economic model in half – Jim Crow the social complex solidified in the hearts of southern whites.[3] This anger further fuelled the severity of racist beliefs among whites which in turn intensified the adherence to segregational norms, white supremacist politicians and violence towards the black community. This is evident in the proliferation of lynchings in the period 1877-1950 where 4,000 were recorded as happening, but is likely to be much higher. Lynchings had been prevalent during slavery, as punishment for escapees that didn’t make it, and so was an attempt to restore an older tradition of southern culture; a social maintenance of the Confederacy.

De Facto Jim Crow, and by extension the social meaning of lynchings was nowhere more exemplified than in the Colfax Massacre of 1873. Lynching was not only the actual act of hanging, but a metaphor for the inhumane murder methods hundreds of thousands of black Americans experienced in their final moments during the Jim Crow era alone.[4] De Facto Jim Crow was a long term historical trend in American history since its seeds were sown in the 17th Century. Without its social construction, maintenance and development, US society would not have produced the type of racialised system, nor the racist politicians that went on to create De Jure Jim Crow, which legalised and enforced the De Facto Jim Crow belief system of racist white America.

[1] Federico, C. M. & Luks, S. The Political Psychology of Race. Columbus: ISPP, 2005

[2] Woodward, C. V. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994

[3] Federico & Luks. The Political Psychology of Race.

[4] Wells, I. B. “Lynch Law in America”. Digital History.

Jim Crow De Jure Legacy

Through a short discussion of the origins of De Facto Jim Crow, it is evident that its impact upon the state of social relations, especially in the South was tremendous. However, it is only when legislation at all levels of governance, beginning with the Supreme Court, that Jim Crow as a whole is unleashed upon American Politics & Society. This institutionalisation of Jim Crow authorised actionable attitudes of (mainly) Southern whites to simultaneously disenfranchise black Americans and facilitate the expansion of white America. The Supreme Court, with the support of the Federal Government, led the charge against the Re-Constructive Era’s extension and protection of Civil Rights for black Americans. Within anti-black legislation there was both a civilian and criminal aspect to control over black freedom.

Historically, Jim Crow De Jure sprouted from ‘Black Codes’ which, after the Civil War, were based on Vagrancy Laws. Black freedmen prior to the Civil War and then all black Americans had to prove when asked by officials (a lot of the time any white) that they held a job that was recognised. If not, they could be arrested. Under the 13th Amendment of 1865, Slavery was illegal UNLESS as punishment for a crime; making the legal system a gateway to the reintroduction of slavery.[1] Prison (black) labour was used in public works in every Southern state, with ‘convict leasing’ a commonly used practice by southern businesses and wealthy individuals to acquire free labour. As Douglas Blackmon wrote it was “slavery by another name”[2]. On the outside of the prison-slavery complex, black Americans were further subjugated to restrictive legal chains. Linking directly to the 1872 Louisiana State election and the subsequent Colfax Massacre, the 1876 ruling ‘US v Cruikshank’ was a shattering legal statement that did much to empower the De Facto enforcers of Jim Crow.

This legal ruling stated that the Bill of Rights did not limit the power of private actors or state governments, empowering them to continue discriminatory practices against black Americans within and without the legal system.[3] This ruling essentially invalidated the 14th Amendment (1868) and the Enforcement Act (1870) both of which were crucial to the emancipation of black America, especially in the South. This early ruling allowed State Jim Crow Laws to develop over the next 20 years, which by 1896 were set to be even further emboldened by them. Plessy v Ferguson (1896) was the final nail in the Re-Construction coffin; again subverting the 14th Amendment and establishing the ‘separate but equal’ legal doctrine that came to define 20th Century Jim Crow.[4] This ruling confirmed the trend away from egalitarianism and an official endorsement of segregation de jure.

On the other side of society, white American’s benefitted from a focus on the expansion of their freedoms and a more direct adherence to the achievement of life, liberty and the pursuit happiness found in the Constitution. This had been set in motion even during the Civil War through the Homestead Act (1862), expanding America to territorially encapsulate and colonise the majority of the northern continent to the current borders of the United States. The Dawes Act (1887) built upon this, after a bloody campaign against Native Americans, tribal lands, borders and people were ripped up from their roots to make way for Manifest Destiny, and allow for European sedentary settlement.[5] Through this conjunction of anti-black and pro-white Federal legislation De Jure Jim Crow embedded itself into the foundations of the US; utilising and expanding the De Facto belief systems that had been brewing for nearly 300 years by the end of the 19th Century.

[1] Lincoln, A. “The Constitution: Amendments 11-27”. The National Archives.

[2] Blackmon, D. A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books, 2008.

[3] Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name.

[4] Kelley, B. L. M. Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v Ferguson. Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

[5] Pratt, J. W. The Origin of “Manifest Destiny”. Washington: Oxford University Press, 1927.

Jim Crow Terrorism

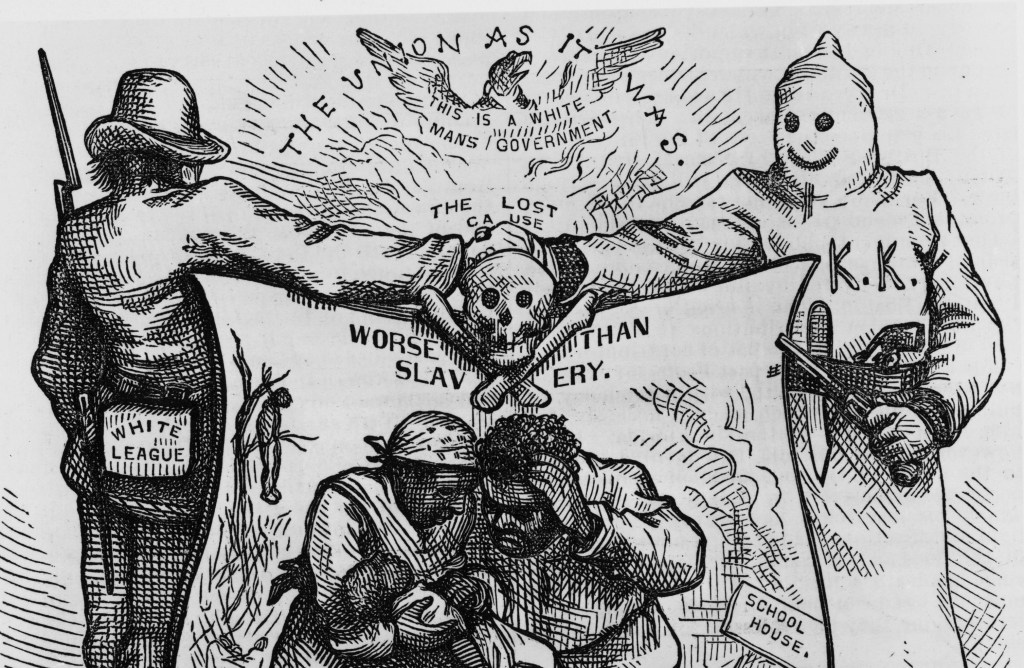

As a testament to the extent of the intertwined connection between De Facto and De Jure Jim Crow, a historian can look no further than the emergence and actions of domestic terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), White League and Red Shirts. In particular, the KKK as a private actor in Southern society had an untold effect upon the development of US racial politics in the 19th and well into the 20th Centuries. Through the use of extrajudicial means the KKK actively sought to undermine and replace Republican governance in the South and further afield, with the vast majority of this being undertaken through the direct targeting of black Communities wherever they existed.

Whilst State legislatures passed grandfather clauses, literacy tests and poll taxes (limiting the legal rights of black Americans) the KKK held a reign of terror across the South, using violence as a method to intimidate, mutilate and murder black Americans in order to maintain the political dominance of white supremacy.[1] This was a complete subversion of the 15th Amendment (1870) and the Civil Rights Act (1866) guaranteeing each citizen the right to vote freely in State and Federal elections. In the case of North Carolina between 1868-70, Klan terrorism was already in full effect, even prior to the removal of Federal protections after the Re-Construction Era.[2]

By the middle of 1869, 15 murders and 100s of lesser atrocities had already occurred constituting severe psychological anxiety on the part of the surviving black community and Republican politicians whom bore arms in fear of their own safety from ‘Vigilante Justice’. Olsen delineates the state of affairs in North Carolina concisely; “Crime and violence of every sort ran unchecked until a large part of the South became a veritable hell through misrule which approximated anarchy…”.[3] This level of violence continued and expanded in the years after, catalysed by the wave of De Jure Jim Crow that was disseminated downwards from the top of American political circles, and would go on to last a further 100 years until the 2nd Civil Rights Era.

[1] Rabinowitz, H. N. From Exclusion to Segregation: Southern Race Relations,1865-1890. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976.

[2] Schaefer, R. T. The Ku Klux Klan: Continuity and Change. Atlanta: CAU, 1971.

[3] Olsen, O. H. The Ku Klux Klan: A Study in Reconstruction Politics and Propaganda. Raleigh: North Carolina Historical Review, 1962.

Conclusion

Through this short discussion of the development of Jim Crow to its systemic height in 1900, it can be seen that the De Facto and De Jure aspects are inseparable from each other. Indeed this symbiotic relationship is exactly what allowed Jim Crow to seep into all levels of American politics and society during the 19th Century and further yet into the 20th Century. The long term cultivation of racial psychology in white society developed the ideology that became institutionalised in the post Re-Construction Era and beyond, forming legal jurisdictions that would entrench socially constructed beliefs into physically constructed barriers, dividing a nation in racial halves for over a century. The simultaneous disenfranchisement of black Americans and enfranchisement of white Americans had a dualistic effect, giving white America two legs up and kicking black America twice in the stomach. Vitally, it was private actors such as the KKK which kept traditional American society in check, with their ranks filled with working class to elite men, they were legally allowed to ensure Jim Crow maintained as a social and political system of control and maintain black disunity and disengagement. The white American socio-political complex worked as a fluid machine with one goal; to suppress all others to ensure their own growth – that machine would be known as Jim Crow.

References

Blackmon, D. A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books, 2008.

Woodward, C. V. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Lincoln, A. “The Constitution: Amendments 11-27”. The National Archives. Accessed Nov 15, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/amendments-11-27

Wells, I. B. “Lynch Law in America”. Digital History. Accessed Nov 15, 2022. https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=1113

Olsen, O. H. The Ku Klux Klan: A Study in Reconstruction Politics and Propaganda. Raleigh: North Carolina Historical Review, 1962.

Schaefer, R. T. The Ku Klux Klan: Continuity and Change. Atlanta: CAU, 1971.

Federico, C. M. & Luks, S. The Political Psychology of Race. Columbus: ISPP, 2005.

Pratt, J. W. The Origin of “Manifest Destiny”. Washington: Oxford University Press, 1927.