Over the last several years, there has been a rising propagation of Islamist extremism globally, which poses substantial obstacles to global security and societies at large. The objective of this literature review is to critically assess the claim that Islamist extremism mostly arises as a response to external threats. This perspective delves beyond the scope of the reductive notion that extremism is only in response to foreign military and political endeavours. However, this review attempts to provide a comprehensive assessment, taking into account several elements, including ideological influences, political circumstances, economic conditions, and social dynamics. Therefore, this review aims to present an exhaustive insight into the varying dynamics of Islamist extremism by thoroughly analysing these factors.

The claim that Islamist extremism is primarily a reactive occurrence, stimulated by external threats, has garnered support among lawmakers, scholars, and media analysts. This stance suggests that activities such as foreign armed operations, governmental interference by foreign powers, or social intrusions from western nations spark extremist ideas and activities inside Islamic communities (Pettinger, 2015). Additionally, Gibbs (2005) affirms that gaining a comprehensive insight into the veracity and consequences of this claim is of utmost importance, as it significantly influences both the way the general public perceives Islamist extremism and the tactics implemented in order to combat it. Although the importance of this theme transcends

the scholarly debate, it has substantial practical consequences. The context in which we discover the roots and motives of Islamist extremism has a profound impact on counter-terrorism approaches, diplomatic relationships, and attempts to foster peace and security in impacted areas (Prinsloo, 2018). An imprecise or premature comprehension of these factors may result in inefficient or potentially destructive methods of addressing extremism.

Consequently, this literature review is motivated by a discerning statement: whilst external threats certainly play a role in the emergence of Islamist extremism, an in-depth inquiry should further include internal factors, notably ideology, political factors, socio-economic circumstances, and social issues. This review is aimed at offering a comprehensive evaluation of the claim by incorporating a range of factors. The intent is to offer a broader and more practical perspective on Islamist extremism. In addition to refuting the claim that extremism is just a reactive response, this strategy advocates a greater understanding of the intricate interactions between numerous factors.

A Foundational Background

Islamist extremism, a concept often used in scholarly, governmental, and media debates, necessitates a precise and comprehensive definition. It often denotes an extremist ideology that centres around a certain perspective of Islam, aiming to construct a social framework governed by diligent obedience to Sharia principles, which may employ violent approaches (Rane, 2016). Moreover, Cook (2015) affirms that Islamist perceptions of extremism suggest the notion that semi-secular or secular governments are misleading because they neglect Islamic principles. This concept spans a broad range of categories, encompassing individuals attempting to impose control upon political decisions within the current structure of nations to those striving to construct totally autonomous states and caliphates.

Historically, the emergence of Islamist extremism is likely to be associated with a range of political, social, and ideological factors that transpired throughout the twentieth century (Esposito & Voll, 1996). Significant events encompass the period after the end of colonial rule, during which Islamic-majority nations underwent the process of establishing their own national identities, and the subsequent political instability and local disputes that followed (Hossain, 2015). These circumstances created a conducive environment for the emergence of extremist beliefs as reactions to what they considered the mistreatment and inadequacies of secular governing systems. In this scenario, the term external threats would refer to actions or interference by other nations that are seen as attacks upon Islamic culture and principles (Weimann, 2010). These factors involve military incursions, interference in politics, and economic measures deemed oppressive or inequitable (Nesser, 2019). An analysis of Islamist extremism as a response to external threats necessitates an examination of how extremist organisations have traditionally utilised such actions to explain their ideology and practices. This method involves meticulous differentiation among the wide range of Islamic ideologies and the particular, often politicised, perceptions that form the foundation of Islamist extremism.

The Role of External Threats

The substantial influence of external threats in contributing to Islamist extremism is adequately presented through the history of foreign intrusions and foreign interferences in domestic politics (Waheed, 2014). Two particularly prominent examples are the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989 (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2023) and the USA’s declared War on Terror that followed the attacks of 9/11 (Bush Foundation, 2013). Extremist organisations see these military deployments as blatant attacks on Islamic communities, which strongly incites them to mobilise and attract new members to engage in resisting them (Karacan, 2020). This is especially evident in the context of Afghanistan, in which the mujahideen’s struggle in opposition to the Soviet invasion eventually turned into a breeding ground for a number of extremist groups, such as Al-Qaeda, Maktab al-Khadamat, the Taliban and many more (Gerges, 2009; Pettinger, 2015).

Foreign nations and their political meddling have significantly contributed to the situation, particularly in the region of the Middle East (Hinnebusch, 2003). The endorsement of autocratic governments by nations in the West, which is regarded as eroding Islamic principles in favour of secularism or Western agendas, has proven to be a recurring source of debate (Nugent et al., 2018). In addition to disrupting regional political systems, this alleged intervention in nations with a plurality of Muslims feeds the notions of oppression and struggle within extremist Islamic groups. Moreover, such groups frequently interpret the dissemination of Western social and liberal ideals as a threat to Islamic values (Adamson, 2005). This belief in cultural imperialism reinforces the extremist notion that Islamic heritage and principles are being challenged by foreign powers, demanding a reactive approach.

The emergence of Islamist extremism is closely connected to these external threats, which act simultaneously as a rationale and a trigger for radicalization. Extremist organisations mobilise solidarity and legitimise their activities in the minds of their supporters by using the narrative of protecting Islam against foreign danger (Rothenberger et al., 2016). The complicated interplay between foreign interventions, involvement in domestic politics, and cultural factors underscores the challenge of comprehending the origins of Islamist extremism. This highlights the necessity for a sophisticated strategy that surpasses simplistic explanations and recognises the complex character of this phenomenon. Esposito (2015), in his scholarly literature, asserts that by promoting cultural warfare in Muslim-West relationships, Western governments have indirectly aided in the growth of jihadist organisations such as Al Qaeda and ISIL. This is a complicated and divisive topic since this stance is based on the notion that the acts and strategies of Western nations might frequently be seen as contributing to a larger social and ideological divide between the West and Islamic society, hence strengthening extremist narratives. Additionally, Pettinger (2015) states that foreign military intervention evokes a negative response in the sense of terrorism, while the nature of the intervention influences the characteristics of the ideology.

When it participates in extensive activities that threaten the sovereignty of other countries and their citizens, the United States specifically appears as an imposing and irresponsible power (Pettinger, 2015). Therefore, extensive involvement often results in the disruption of local power organisational structures, which provides an ideal setting for the emergence of terrorism through Islamic extremism. Kumar (2018) agrees with the fact that the Western critique of Salafism and terrorism perpetuates unfavourable generalisations about Islam, consequently fuelling the growth of Islamophobia, and the outcome of that has been countered by the West in the name of intervention and interference to uphold stability and peace in the region, further declining the region’s stability. This has cultivated an image that depicts Islam in a malicious manner, frequently portrayed as a manifestation of Islamic demonization (Kumar, 2018).

Ideological Factors

A significant aspect that often emerges irrespective of external factors is the role played by religious ideology and political perspectives in fuelling Islamist extremism (Bale, 2013). The objectives and behaviours of extremist organisations might be profoundly influenced by these ideals (Nasr, 2005). Hellmich (2008) as well as Blanc and Roy (2021) assert that ideologies involving certain violent strands of Salafism as well as Wahhabism, which promote a revival of the practices that they perceive and claim as the authentic customs of early Islam, serve as the fundamental principles of extremist organisations such as Al Qaeda, the Taliban and ISIS. These ideologies attempt to reinforce a strict and precise understanding of Islamic scriptures, often disregarding contemporary perspectives and behaviours (Pratt, 2017). The rigid adherence to a certain ideology may foster an atmosphere that promotes extremism, particularly when it is accompanied by a rejection of occidental influences and a demand for the creation of an Islamic state regulated only under the principles of Sharia (Vikør, 1998).

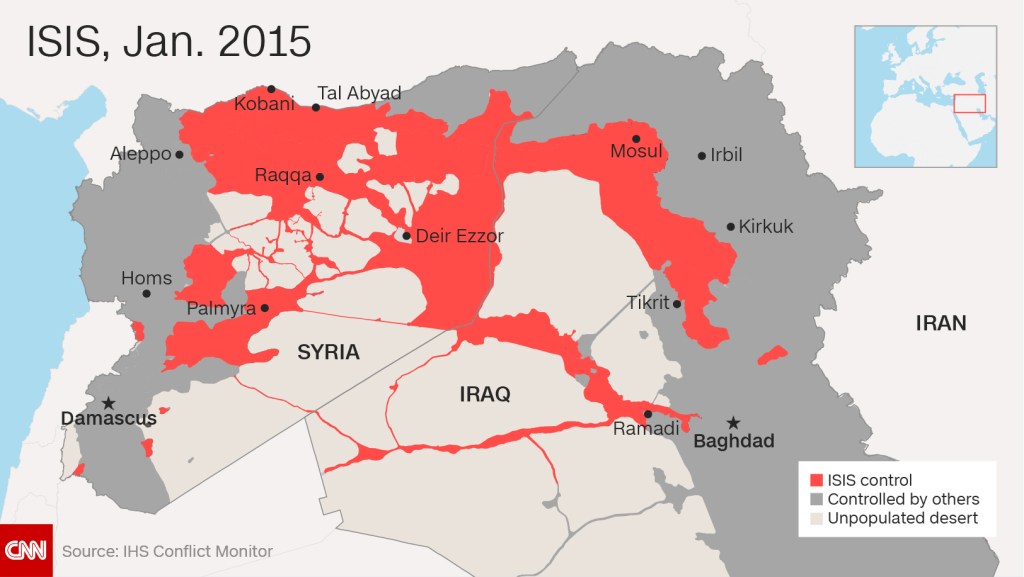

The substantial influence internal ideological notions exert, regardless of external factors, refutes the notion that Islamist extremism is only a response to external threats. The philosophy of ISIS, which combines militant jihadism with eschatological themes from Islamic thought, was not only a reaction to external events. As demonstrated by this internal ideological structure, ISIS’s motives were primarily separate, stemming from an urge to build a society as a whole founded on their understanding of Sharia and its principles. Their desire to go back to those ideals that they perceived to be the true and valid fundamentals of Islam, even in the face of external factors, including foreign interventions, did complicate scenarios. The situation of ISIS exemplifies the intricate nature of Islamist extremism, whereby ideology assumes a pivotal and independent role. Comprehending this facilitates elucidating that although external influences are significant, they do not serve as the only catalysts for these movements. The inherent convictions and understandings inside these factions may autonomously influence their behaviours and objectives, highlighting the necessity for a comprehensive strategy in discussing the origins of Islamist extremism carefully.

Another appropriate instance would be the Taliban in Afghanistan. The Taliban emerged from the mujahideen struggle during the Soviet invasion (Nojumi, 2002). Their core reasons were strongly influenced by the Deobandi doctrine, which is a traditional and conservative interpretation of Islam and opposes contemporary ideas (Misra, 2002). Prior to the Soviet-Afghan struggle, this ideology was already in existence, and it had a profound influence on the Taliban’s methods of governing and establishing laws and regulations (Silinsky, 2014). Their governance in Afghanistan was marked by rigorous devotion to Deobandi doctrines, influencing several aspects ranging from social initiatives to judiciary decision-making (Misra, 2002). Boko Haram in Nigeria, on the other hand, began as an extreme organisation motivated by the radical ideology of violent Salafism and jihadism after being impacted by regional socio-political difficulties (Nachande, 2017). This philosophy, which rationalised the use of force against whom it saw as a nefarious Nigerian government, became a distinguishing feature of the organisation. The evolution of Boko Haram exemplifies how regional concerns may intertwine with overarching ideological narratives, resulting in a powerful combination that drives groups closer to extremism. The transition from local issues to a more encompassing ideological clash is the foundation of Boko Haram’s expansion, illustrating the group’s commitment to an extreme perspective on Islam that rationalises its use of lethal and destructive approaches (Sani, 2021).

Political and Economic Factors

It is crucial to investigate how internal political circumstances affect the propagation of Islamist extremism. The growth of Islamist extremism in several Islamic-majority nations may be attributed to the presence of authoritarian governments and social marginalisation as significant driving elements (Dalacoura, 2006). Authoritarian governance erroneously cultivates extremist beliefs in individuals through the repression of political opposition and marginalisation of communities, especially individuals with Islamist inclinations (Kaya, 2020). These governments often restrict political discourse, provoking opposition through unorthodox and perhaps extreme means (Sarkissian, 2012). For instance, the rise of extremist factions in some regions of the Middle East has been strongly associated with enduring political repression and inadequate representation, indicating a clear connection between political repression and the proliferation of extremism (Dalacoura, 2008).

Economic concerns significantly impact the growth of Islamist extremism, whereby poverty, unemployment, and inequality in wealth emerge as essential components (Zaidi, 2010). Therefore, these circumstances can potentially induce a feeling of despair and isolation, particularly among young individuals, who may also experience a sentiment of disengagement (Lynch, 2008). Extremist organisations commonly exploit these economic difficulties, positioning their own groups as a remedy that provides not only a feeling of belonging but also monetary benefits (Borum, 2011). This method has been especially efficient in areas characterised by an absence of governmental assistance and limited prospects (Suleiman & Karim, 2015). Research has shown a significant correlation between financial difficulties and vulnerability to extremist principles, indicating that economic stress might increase people’s

susceptibility to radical ideologies (Piazza, 2007). Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that while economic reasons play a substantial role, they don’t serve as the only stimulant for extremism. The intricate structure of radicalism and extremism highlights the intricacy of tackling them, since only implementing economic measures is not enough to combat the appeal of extremist organisations.

When assessing the importance of domestic, political and economic factors that fuel Islamist extremism, it is crucial to consider the impact of foreign threats, as mentioned earlier as well. The existing literature on the issue provides a dichotomous perspective: some scholars highlight the prevalence of foreign interventions, while others concentrate on the significance of domestic dynamics. Scholars like Naumkin (2014) and Pettinger (2015) argue that the only stimulant that fuels Islamic extremism is foreign intervention, which inevitably provokes adverse reactions in the form of terrorist activities, with the specific form of the intervention playing a crucial role in shaping the extremist ideology that arises as a consequence. This becomes more apparent when these interventions entail substantial undertakings that jeopardise the autonomy of other nations and their inhabitants. However, scholars including Borum (2011) and Pipes (2001) concur with Zaidi (2010) that the rise of extremism is not only attributable to external threats. They highlight that factors including poverty, misrepresentation, political suppression, and income inequality also play critical roles as catalysts for Islamic extremism.

Social Conditions and Influences

Social marginalisation and alienation significantly contribute to the growth of extremism, exerting a strong influence on people and groups that experience exclusion from society (Bull & Rane, 2018). Experiencing a feeling of being marginalised, which is often caused by characteristics such as race, religion, or economic status, makes people more vulnerable to extreme perspectives (Syed & Ali, 2020). Instances of prejudice or perceived mistreatment based on one’s identity might intensify feelings of alienation in individuals (Sadek, 2017). Consequently, a lack of societal progress might intensify the perception of being isolated or ignored, further exacerbating the perception of alienation. Extremist groups adeptly capitalise on these sentiments of marginalisation and estrangement (Khalaf & Khalaf, 2012). They provide a communal atmosphere, a space where people experience empathy and a feeling of belonging (Moghaddam, 2004). This proposition may be especially appealing for individuals who have consistently been marginalised by their own communities. Moreover, such organisations present a narrative that substantiates the issues of marginalised people, presenting their fight as a righteous mission against the injustice they have faced using violent means only.

There are many substantial effects of education and the media on the growth of Islamic extremism (Shadid & Van Koningsveld, 2002). The media and its extensive reach contribute to an instrumental influence in moulding public opinions and perspectives about Islamist extremism (Matthes, 2010). The repeated portrayal of Islamic communities in an inaccurate or stereotyped way by media sources has fostered a social climate characterised by distrust and paranoia (Smith & Akbarzadeh, 2005). Consistently witnessing poor portrayals of their identity might exacerbate feelings of being misinterpreted or demonised for these individuals. Therefore, extremist organisations often use these narratives created by the mainstream media, positioning themselves as advocates opposing social inequities and prejudice. Education nevertheless influences the fundamental outlooks and beliefs of citizens, especially young people. Restrictive or biased learning environments may restrict individuals’ access to a wide range of views, hindering their capacity to analyse and interact with varied perspectives in an analytical manner. Therefore, if educational environments or institutions promote extremist opinions or neglect to question extreme ideology, they may foster the vicious cycle of extremism and violence (Afrianty, 2009).

Conclusion

Upon examining each aspect of this literature review, it becomes evident that the rise and propagation of Islamist extremism are shaped by an intricate interaction of external and internal factors. This complex causality undermines the basic theory suggesting that Islamist extremism is only a reactive response to external threats. The research demonstrates that while external influences, such as foreign military operations and political meddling, certainly have a substantial impact, they are not the only explanation for the emergence of such extremism. Internal factors, such as political repression, socio-economic inequality, ideological influence, and social estrangement, play a crucial role in the rise and spread of Islamic extremism. There are significant repercussions when it comes to policy formation and tactical interventions when Islamist extremism is framed as a reaction to external factors alone. Adopting a narrow viewpoint runs the danger of oversimplifying a multifaceted problem, which might result in ineffective and ignorant approaches. For example, a policy that primarily emphasises military intervention may neglect the crucial need to deal with underlying problems such as systematic and political exclusion, economic suffering, and educational shortcomings that lead to extremism. This thorough review emphasises the need for an integrated approach to comprehending and tackling Islamist extremism. It is essential for policymakers and future researchers to carefully analyse both external and internal factors in their decision-making and research. It is essential to implement policies that aim to promote inclusive political settings, stimulate economic development, and modernise educational institutions in areas that are susceptible to extremism. Future studies should further investigate the complex interconnections among these diverse elements. The objective of this strategy is to cultivate more efficient and enduring methods for combating extremism based on an in-depth assessment of its complex characteristics.

References

Adamson, F. B. (2005). Global Liberalism versus Political Islam: Competing Ideological frameworks in International Politics1. International Studies Review, 7(4), 547–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2486.2005.00532.x

Afrianty, D. (2009). Islamic education and youth extremism in Indonesia. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, 7(2), 134–146.

https://doi.org/10.1080/18335330.2012.719095

Bale, J. M. (2013). Denying the Link between Islamist Ideology and Jihadist Terrorism: “Political Correctness” and the Undermining of Counterterrorism “Political Correctness” and the Undermining of Counterterrorism. Perspectives on Terrorism, 7(5), 5–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26297006

Blanc, T., & Roy, O. (2021). Salafism, challenged by radicalization?: Violence, Politics, and the Advent of Post-Salafism.

Borum, R. (2011). Radicalization into Violent Extremism II: A Review of Conceptual Models and Empirical Research A Review of Conceptual Models and Empirical Research. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(4), 37–62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26463911

Bull, M., & Rane, H. (2018). Beyond faith: social marginalisation and the prevention of radicalisation among young Muslim Australians. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 12(2), 273–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2018.1496781

Bush Foundation. (2013). Global War on Terror. George W. Bush Library. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.georgewbushlibrary.gov/research/topic-guides/global-war-terror

Cook, D. (2015). Understanding Jihad [eBook]. University of California Press.

Dalacoura, K. (2006). Islamist terrorism and the Middle East democratic deficit: Political exclusion, repression and the causes of extremism. Democratization, 13(3), 508–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340600579516

Esposito, J. L. (2015). Islam and political violence. Religions, 6(3), 1067–1081.

https://doi.org/10.3390/rel6031067

Esposito, J. L., & Voll, J. O. (1996). Islam and democracy. Oxford University Press.

Gerges, F. A. (2009). The Far Enemy: Why Jihad Went Global (2nd ed.) [eBook]. Cambridge University Press.

Gibbs, S. R. (2005). Islam and Islamic Extremism: An Existential analysis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 45(2), 156–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167805274728

Hellmich, C. (2008). Creating the ideology of al Qaeda: from hypocrites to Salafi-Jihadists. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 31(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100701812852

Hinnebusch, R. (2003). The international politics of the Middle East.

https://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9780719053450.001.0001

Hossain, A. A. (2015). Contested National Identity and Political Crisis in Bangladesh: Historical analysis of the dynamics of Bangladeshi society and politics. Asian Journal of Political Science, 23(3), 366–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2015.1073164

Karacan, T. B. (2020). Reframing Islamic State: Trends and themes in contemporary messaging. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/249924

Kaya, A. (2020). State of the Art on Radicalization: Islamist and Nativist Radicalization in Europe. ResearchGate.

Khalaf, S., & Khalaf, R. S. (2012). Arab Youth: Social Mobilisation in Times of Risk [eBook]. Saqi.

Kumar, H. (2018). How Violence is Islamized. International Studies, 55(1), 22–40.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0020881718761768

Lynch, O. (2008). Suspicion, Exclusion and Othering since 9/11: The Victimisation of Muslim Youth. Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks, 173–200. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137347114_8

Matthes, J. (2010). Mass media and public opinion: Manipulating or enlightening. Dialogue on Science.

Misra, A. (2002). Review: The Taliban, Radical Islam and Afghanistan. Third World Quarterly, 23(3), 577–589. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3993543

Moghaddam, F. M. (2004). From the Terrorists’ Point of View: What They Experience and Why They Come to Destroy. Praeger.

Nachande, C. K. (2017). Beyond Terrorism and State Polity: Assessing the Significance of Salafi Jihad Ideology in the Rise of Boko Haram. Journal of Pan African Studies, 10(9).

Nasr, V. (2005). The Rise of “Muslim Democracy.” Journal of Democracy, 16(2).

Naumkin, V. (2014). Middle East Crisis: Foreign Interference and an Orgy of Extremism. Valdai Discussion Club.

Nesser, P. (2019). Military interventions, Jihadi networks, and terrorist entrepreneurs: How the Islamic state terror wave rose so high in Europe. CTC Sentinel, 12(3), 15–21.

Nojumi, N. (2002). The rise of the Taliban. In Palgrave Macmillan US eBooks (pp. 117–124). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-312-29910-1_11

Nugent, E., Masoud, T., & Jamal, A. A. (2018). Arab Responses to Western Hegemony: Experimental Evidence from Egypt. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(2), 254–288. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48597297

Pettinger, T. (2015). What is the impact of foreign military intervention on radicalization? Journal for Deradicalization, 5, 92–119. https://journals.sfu.ca/jd/index.php/jd/article/view/36

Piazza, J. A. (2007). Rooted in Poverty?: Terrorism, Poor Economic Development, and Social Cleavages1. Terrorism and Political Violence, 18(1), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/095465590944578

Pipes, D. (2001). God and Mammon: Does Poverty Cause Militant Islam? The National Interest. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42897457

Pratt, D. (2017). Religion and Extremism: Rejecting Diversity. https://boris.unibe.ch/113736/

Prinsloo, B. L. (2018). The etymology of “Islamic extremism”: A misunderstood term? Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1463815. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1463815

Rane, H. (2016). Narratives and counter-narratives of Islamist extremism. In Routledge eBooks (pp. 167–185). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315692029-10

Rothenberger, L., Müller, K. M., & Elmezeny, A. (2016). The discursive construction of terrorist group identity. Terrorism and Political Violence, 30(3), 428–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2016.1180288

Sadek, N. (2017). Islamophobia, shame, and the collapse of Muslim identities. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 14(3), 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/aps.1534

Sadek, N. (2017). Islamophobia, shame, and the collapse of Muslim identities. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 14(3), 200–221.

https://doi.org/10.1002/aps.1534

Sani, M. M. (2021). Exploring the role of ECOWAS’s conflict prevention framework in the light of a terrorist insurgency: The case of Boko Haram in northern Nigeria [Thesis]. University of Manitoba.

Sarkissian, A. (2012). Religious regulation and the Muslim democracy gap. Politics and Religion, 5(3), 501–527. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1755048312000284

Shadid, W. a. R., & Van Koningsveld, P. S. (2002). Religious freedom and the neutrality of the state: The Position of Islam in the European Union. Peeters Publishers.

Silinsky, M. (2014). The Taliban: Afghanistan’s Most Lethal Insurgents. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Smith, B., & Akbarzadeh, S. (2005). The representation of Islam and Muslims in the media. School of Political and Social Inquiry, 4.

Suleiman, M. N., & Karim, M. A. (2015). Cycle of bad governance and corruption. SAGE Open, 5(1), 215824401557605. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015576053

Syed, J., & Ali, F. (2020). A pyramid of hate perspective on religious bias, discrimination and violence. Journal of Business Ethics, 172(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04505-5

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2023, October 18). Soviet invasion of Afghanistan | Summary & Facts. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Soviet-invasion-of-Afghanistan

Vikør, K. S. (1998). The Sharia and the nation state: who can codify the divine law? The Middle East in a Globalized World.

Waheed, A. W. (2014). Sovereignty, failed states and US foreign aid: a detailed assessment of the Pakistani perspective [PhD Dissertation]. Queen Mary University of London.

Weimann, G. J. (2010). Islamic criminal law in northern Nigeria: politics, religion, judicial practice [MA Thesis]. University of Amsterdam.

Zaidi, S. M. A. (2010). The poverty–radicalisation nexus in Pakistan. Global Crime, 11(4), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2010.519521